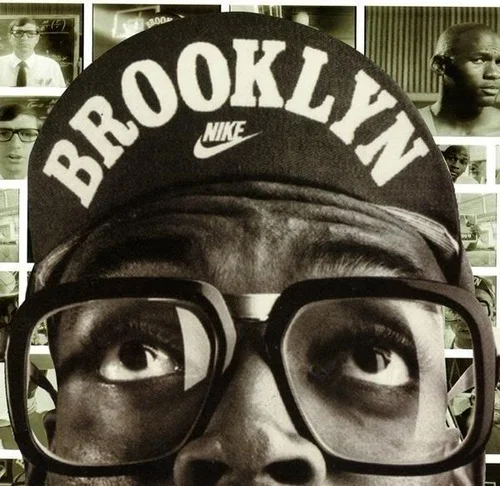

The Real Spike Lee Story

originally published on artluxmag

Contrary to what was covered in the media, Spike Lee didn’t just address the issue of Brooklyn gentrification last Tuesday at the Pratt Institute in Clinton Hill. The famed film director critiqued Black youth culture’s relation to education, discussed the politics of accurate depictions of people of color in film and talked about his come-up in the film industry. However, instead of contextualizing the discussion, the media sensationalized Lee’s remarks. Then, three days after his frank observations about racial, economic, and cultural transformations of Brooklyn neighborhoods were published on all major news networks and blogs, from CNN to Gawker, Lee’s father’s home in Fort Greene was vandalized. “Do the Right Thing” and the anarchy symbol was spraypainted on the street level of their brownstone.

“Why does it take an influx of White New Yorkers in the South Bronx, in Harlem, in Bed Stuy, in Crown Heights for the facilities to get better?,” was the quote that lassoed the crux of his passionate remarks on gentrification. The question seemed relevant as Lee was addressing an audience at one of the premiere art and design schools in the nation that has facilitated much of the gentrification in Clinton Hill and its surrounding areas. Most news outlets described it as an emotional “rant,” another outburst from an angry minority and left it at that. But those remarks were couched in a hotbed of information about Lee’s background growing up in Brooklyn when there weren’t cake-pop stores or fancy vegan, gluten-free bakeries. In the Fort Greene of Spike Lee’s adolescence, Myrtle Avenue was called Murder Avenue.

What you didn’t hear from the blurbs and sensational reports was that Spike Lee came from a highly educated family. His father was a Morehouse college graduate and jazz musician. His mother was an art teacher. His grandmother, who was two generations removed from slavery, had a degree from Spelman College in Atlanta and taught art for 50 years. Lee’s family was highly supportive of his career in filmmaking. “Spikey, whatever you want to do, I support you,” his grandmother said. And with her social security checks, Lee’s grandmother put him through Morehouse College, film school at Clark Atlanta University, and graduate school at NYU.

If anything, Lee’s parents pushed him to excel. When he got an A his mother would respond with, “Don’t you know you have to be ten times better?” This is the “model minority” complex most people of color face in institutional education. Getting A’s and B’s is simply not good enough when society does not expect you to attend higher education. Lee referenced the high school graduation rate for black males as being close to 50% (in 2010 it was 52%, up from 47% in 2008). For Lee and a lot of his classmates, higher education and particularly artistic endeavours were an unattainable dream without scholarships, extra attention from educators and family support. However, Spike Lee had those family and teacher advocates. Even in college, a professor at Morehouse took special interest in him and spent hours after class helping him edit films.

So Spike Lee is a very special case in how a Black kid from the hood achieves success. His mix of opportunities are rare for a lower middle class kid of color: supportive family, educated family, grandma with the funds, luck (a friend gave him his first super 8 camera for free,) talent that was noticed by an educator, and extra help by that educator. He had a lot of people on his side, working to see him succeed.

And you know what? I think Spike Lee knows this. He has the unique subject position to be able to see things from several sides, and he has the platform to be heard. He grew up in Fort Greene Brooklyn when the trash wasn’t being picked up, there was no police protection, parks and schools were a mess, which brings us to: “why did it take this great influx of White people to get the schools better? Why is there more police protection in Bed Stuy and Harlem now? Why is the garbage getting picked up more regularly? We been here!" With White newcomers to the neighborhood, rents went up, availability of resources went up and people of color were pushed out of their own neighborhoods. And this continues today. Why is it that when a person of color points out an egregious problem with the system, the headline is bombastic? “Spike Lee goes on 7-minute rant against White hipster gentrifiers” and not “Spike Lee points outs persisting problem of Brooklyn gentrification.” Spike Lee isn’t demonizing White people as a demographic, he’s pointing out a problem with the system that White people consistently benefit from-- a system that historically and consistently pushes people of color to the margins, cutting off access to opportunity and progress.

In addition to gentrification politics, Lee analyzed film production politics after being asked why substantive subjects such as mental illness in Black communities were not being addressed through film. He responded with, “When MGM decided to make Soul Plane, we weren’t in the room.” A group of most likely White men decided it would be a great (i.e. profitable) idea to make a film that reproduces stereotypes about Black people. When that was decided, Black people weren’t there to weigh in their opinions, and that’s why those movies get made. He added that, “It doesn’t matter if we have stars that make $20 million,” if we don’t have the vote on what type of movies get made.

Spike Lee is one of the few stars publicly talking about local politics. His first subject of the night was education and how he’s an advocate of higher education. He expressed dismay at how some of rap culture derides education and how some youth seem to be equating intelligence with acting White and ignorance with being Black. Lee fears an uneducated community that sips 40s on their stoop, “smoking that chunky black.” However, the audience was a bunch of Pratt students and Spike Lee admirers, not really the demographic he should be lecturing to stay in school or to “pull your fucking pants up.” I mean, the Pratt Institute is 5% Black as one of the audience members from the African American Student Union pointed out. But was it the audience who needs to be lectured on gentrification issues and respect for established communities? Yep, sure was. Was it also the community who needs to hear his story and how he made a shining career for himself? Yes, because despite the onslaught of gentrification, Brooklyn is now a very mixed community, and there are still Black families who own houses and businesses in the neighborhood. They were the ones clapping when he said “Fort Greene’s the Mecca. Fort Greene Comes First.”